|

Firstly - This preconceived idea that we should all fit into some "ideal posture" is ludicrous and needs to stop.

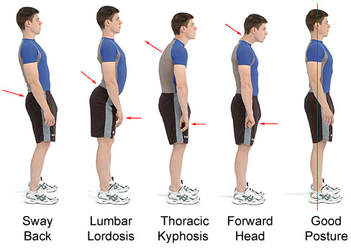

Have you ever heard someone say that your chest is too tight and that you need to train your back muscles more in order to get your shoulders to sit back and to improve your posture? Ever heard the one about weak glutes and tight hip flexors causing your bum to stick out? The common practice where trainers and therapists suggest that a muscle is weak or tight and is causing poor posture is actually negligent and could be considered malpractice. Most postural things you see are not due to weakness or tightness (Tom Purvis, 2015). In addition to this, we certainly cannot tell if a muscle is weak just by looking at someone’s posture. Why wont training a muscle help improve my posture? Training a muscle won’t make you automatically sit in a specific position. Training your back won’t make your shoulders sit back. Training your bicep won’t make your elbow sit at a 90 degree angle. Training your hamstrings won’t make your leg kick backwards. Training your shoulders won’t make your arm sit at a 90 degree angle. Simply strengthening a muscle does not necessarily mean that it will move to a different resting position. It may mean that you have to use less effort to overcome gravity to get to that position you consider as “good posture”. However, it won’t mean you automatically sit in that position. A possibly more effective way to think about posture is that it is all about HABIT and BODY STRUCTURE. Changing your Habits A quick exercise you can do is to simply stand tall and stick your chest out. How do you look? If you can get into a position that you would consider to be “good posture” then maybe you don’t have any muscular weakness or tightness preventing you from being in that position. Maybe you can develop a habit of putting yourself into that position more often over time. If it’s something you want to achieve then it might be a good idea to practice it regularly. In this case it is likely as simple as that. Structural Considerations If you cannot get into a position that you would consider “good posture” then there could be a myriad of things happening that are preventing this. Some of these might include:

Overall, posture is highly individual and will vary greatly between clients. It might not be a good idea to try to jam someone into a posture that their structure simply does not allow for. Instead of always looking to “correct” posture, have a think about what has caused that posture in the first place and whether it actually needs to be changed for that person to function and train effectively. References: Personaltrainingdotcom, 2015, Perspective: “Correcting” Posture (online video) avaiable at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yNWDwE7-cS0&t=357s Delavier, F. (2010). Strength training anatomy. Leeds: Human Kinetics.

1 Comment

Compensation is an essential part of life. Every time you ask your body to move, it needs to figure out the solution, and it's going to take the easiest most efficient solution every time. When everything is working this is great, however when there is dysfunction in the muscular system it can be problematic.

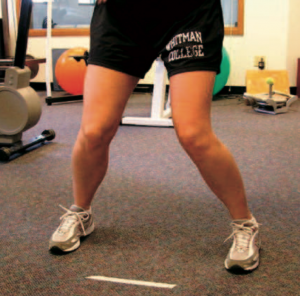

In Biology "compensation" is defined as the improvement of any defect by the excessive development or action of another structure or organ of the same structure1. A google search came up with "Something that counterbalances an undesirable or unwelcome state of affairs." When talking about exercise, compensation occurs when someone loses the ability to utilise one or more parts (muscles) to perform a movement. Other muscles then provide a greater contribution to enable this movement to occur. This may or may not be a big deal depending on the individual, their training goals and body structure. When injuries develop, your body might not have access to all the "parts" it did before the injury. For instance imagine you've rolled your ankle playing basketball. During the injury recovery process, your body will call upon other muscles to allow you to keep walking while you recover. Once the ankle is back in normal working order, you will hopefully go back to walking the way you did before the injury. If you don't actively work on restoring strength in the ankle, then this compensation might continue and could start to weigh on passive structures of the body (bone, ligaments, joints etc). This can lead to the development of more chronic pain. Hence the importance of improving the contractile efficiency of muscle during the rehabilitation process. The same thing applies to performing exercise in the gym. If a muscle can't elicit a contraction, then your body is likely to compensate to solve the movement problem you have presented it with. For instance, the above image shows someones knees falling in during a squat. This might be fine depending on the individuals structure, goals, current settings and their capabilities. However instances might occur where this places load on passive structures, pushing them into positions they don't want to go. If action isn't taken to address the limitations in muscle contraction, then this might lead to inflammation and injury of the ligaments of the knee. Note the solution to this problem might not be to simply tell the client to "shove their knees out"... the solution might be to use a different exercise to strengthen the muscles that enable their knee to push out. Ultimately this is something that needs to be addressed through a full assessment of muscle contractile capabilities. Tips to for when compensation becomes problematic: 1) Focus on of the sensation of exercises. If you're feeling joint pain then something needs to be addressed. 2) Activate muscle before you train. Ensure muscle is prepared for the forces you're about to put through your body. There are plenty of specific activation exercises online and on my Facebook page. 3) Get checked out by a professional who understands how to check range of motion and improve muscle contractile efficiency. When competing in sport it is pretty important for the muscular system to be working efficiently. An inhibited muscle can lead to the development of compensation patterns, which can ultimately lead to reduced performance and injury. Since athletes train at an extremely high level, any pre-existing muscular imbalances can get magnified. Once they exceed their tolerance levels, injuries tend to develop. MAT can help athletes in that it enables us to:

Since MAT helps to balance the muscular system, it improves the environment for healing, which can ultimately enable athletes to return to the field sooner. Once an athlete has recovered from injury, MAT can then be used on a regular basis to ensure they remain strong. This is where MAT has possibly the most benefit - Ensuring the muscular system is working at a high level and facilitating optimal performance. Hit the "book now" button and try it out for yourself. Ever had a niggling injury you can't seem to recover from? Ever had joint pain despite no real structural issues? Have you tried stretching, massage and other forms of therapy but not seen any improvement?

In many cases this can be attributed to a lack of contractile efficiency of muscle. When a muscle cannot efficiently contract, load is picked up by either:

The above situations are not ideal as they essentially lead to excessive load being placed on these passive structures. In the long run this can lead to joint deterioration, tendinitis or arthritis. These situations can possibly be remedied/prevented by improving the contractile efficiency of muscle. Muscle is the stuff that supports these passive structures. Through MAT® we can identify which muscles are weak and then take action to strengthen these weaknesses. A MAT® session involves a full assessment of range of motion followed by manual muscle testing, where precise forces are applied to restore the contractile efficiency of muscle. Once an inhibited muscle is able to contract again, it has the potential to take load off passive structures and reduce compensation... which may ultimately restore normal function and reduce pain as a result. Muscle Activation Techniques is all about assessing and correcting muscular imbalances, joint instability and limitations in range of motion in the human body. It is beneficial for:

- Injury rehabilitation - Maximising athletic performance, and - Enabling participation in exercise MAT® Practitioners assess active range of motion in order to determine which muscles are potentially weak. They then look to activate and strengthen muscles that may be weak or inhibited due to stress, trauma or overuse. Often this opens up range of motion and can reduce feelings of tightness, pain or instability. MAT® is based on the principle that flexibility is a derivative of strength and muscle "tightness" is secondary to muscle weakness. A limitation in motion is an indicator that one or more of the muscles that cross that axis cannot contract efficiently. MAT® seeks to identify these limitations and then restore and/or improve the contractile efficiency of muscle. MAT® Sessions are non-invasive in the sense that they do not push people past active ranges of motion. The sessions may involve palpating/massaging the attachment sites of muscle, however this is largely a painless process. MAT® is not about passively "stretching", rather it is about activating and strengthening muscle. If you've got a niggling injury or are experiencing joint pain or muscle tightness, book in a session and see how Muscle Activation Techniques can benefit you. |

AuthorAlex is a Muscle Activation Techniques Practitioner and Resistance Training Specialist. Focused on Injury Rehab and Maximising Performance. Archives

November 2018

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed